Clubs of Bamako

9 MARCH - 16 APRIL 2000

Rice University Art Gallery, in collaboration with The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH), presents Clubs of Bamako, an exhibition of sixteen black and white photographs of the nightclub scene in Bamako, Mali in the 1960s and 1970s, by Malian photographer Malick Sidibé. The photographs are shown with eleven life-size sculptures by contemporary Ivory Coast sculptors Emile Guebehi, Koffi Kouakou, and Coulibaly Siaka Paul. The exhibition at Rice Gallery has been planned to correspond with the opening of the MFAH’s new Audrey Jones Beck Building.

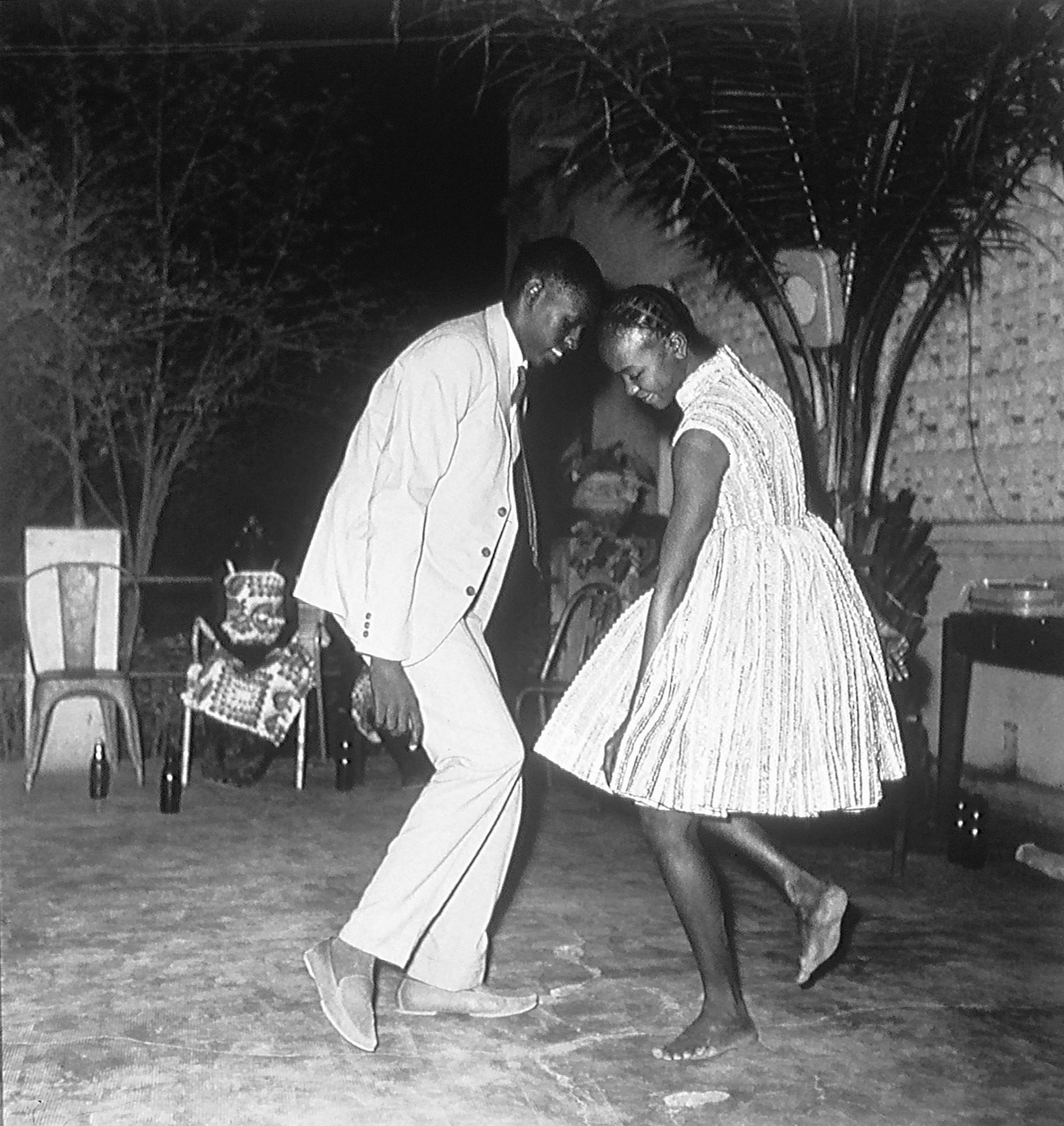

The late 1950s and early 1960s marked the end of colonial rule for much of Africa. With this new freedom came a reexamination of the basis for national and cultural identities that were hybrids of African and Western influences. Malick Sidibé’s photographs capture the vibrancy of this transitional moment. The Malian nightlife he documented was especially lively in this era, when clubs with names like the “Happy Boys Club” and “Les Surfs” played music ranging from Miles Davis and James Brown to local, top-of-the-chart hits like “Mali Twist” by Boubacar Traoré, popularly known as Kar Kar. The clothing worn by Sidibé’s club-goers – miniskirts, bell bottoms and turbans fashioned of wildly patterned local fabrics – equally reveals a culture entrenched in two histories. Sidibé’s interest in the scene stemmed not from the viewpoint of a detached observer, but from his desire to experience “the most joyful and frivolous moments so that I could take the pictures I liked.” The result, says NY Arts Magazine critic Horace Brockington, was that “the clubs and dance halls became his laboratory for photographic experimentation rather than cultural exploitation.”

Adding to the dynamism of Sidibé’s photographs are eleven life-size polychrome wooden sculptures that, along with music of the era, bring the club scene alive in the gallery space. Guebehi, Kouakou and Siaka Paul chose individuals portrayed in Sidibé’s images and rendered them as free-standing, three-dimensional figures frozen in mid-movement. Koffi Kouakou’s carving of a tall African gentleman dressed in a black suit and top hat, stands with legs crossed as if prepared to pivot momentarily. Coulibaly Siaka Paul depicts a couple who while dancing with one another are simultaneously absorbed in their own movements. Emile Guebehi’s woman in a brightly striped miniskirt appears to be moving to a beat that is invisibly present in all of the figures. In the company of Sidibé’s photographs, the sculptures, according to The New York Times art critic Holland Cotter, “feel fresh, vital, and larger than life, but also rooted in time and place.”