Wolfgang Winter and Berthold Hörbelt Kastenhaus

21 SEPTEMBER - 29 OCTOBER 2000

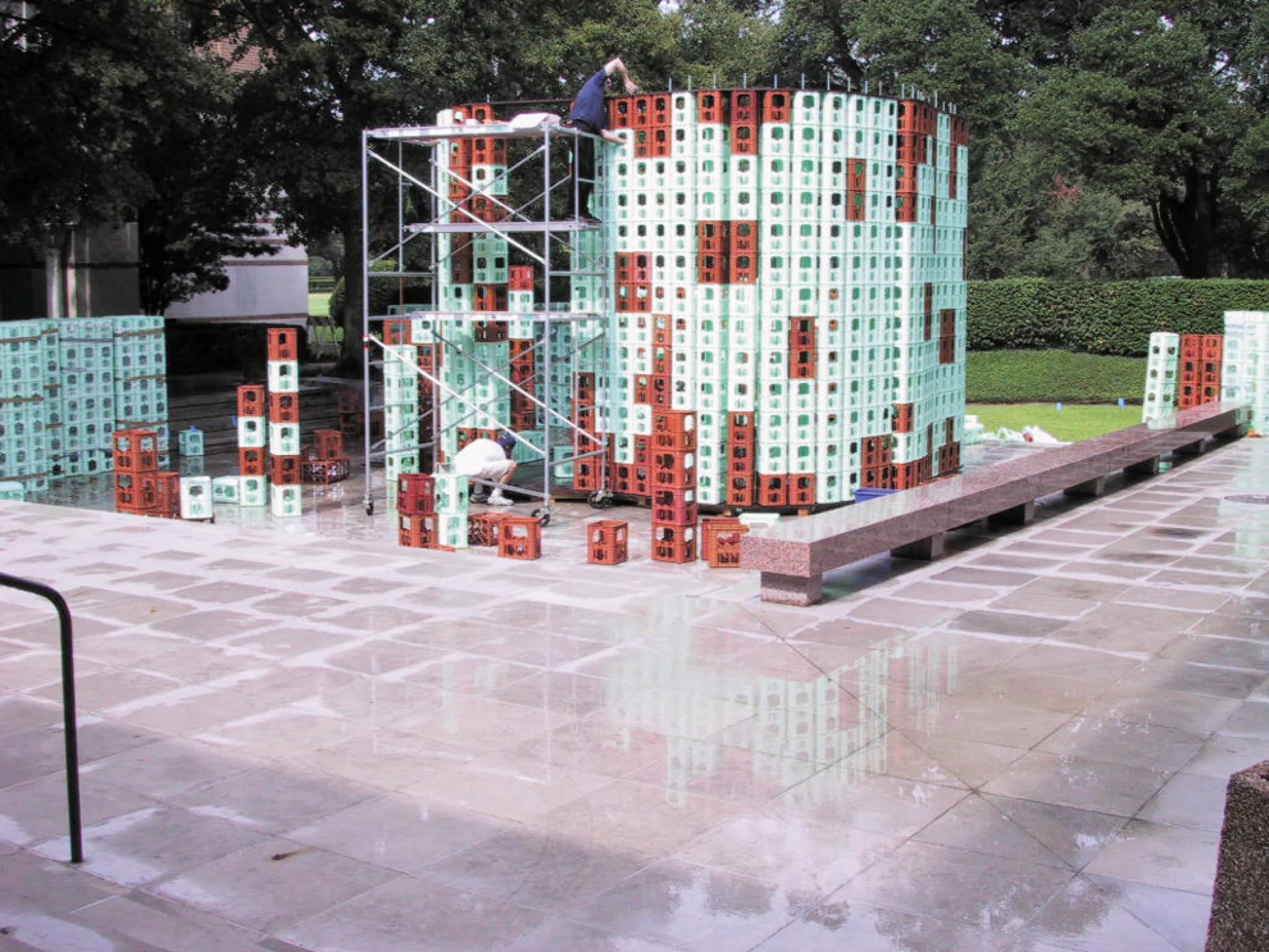

Winter/Hörbelt have received great acclaim for their beverage crate structures, which have been included in numerous international exhibitions including Sculpture Project Münster, 1997; Sao Paulo Biennial, 1999; and the Venice Biennale, 1999. Their project for the Rice Gallery will be constructed on the Gallery Plaza, a major campus crossroads, and will serve as a locus for public gatherings, spontaneous interaction and scheduled events.

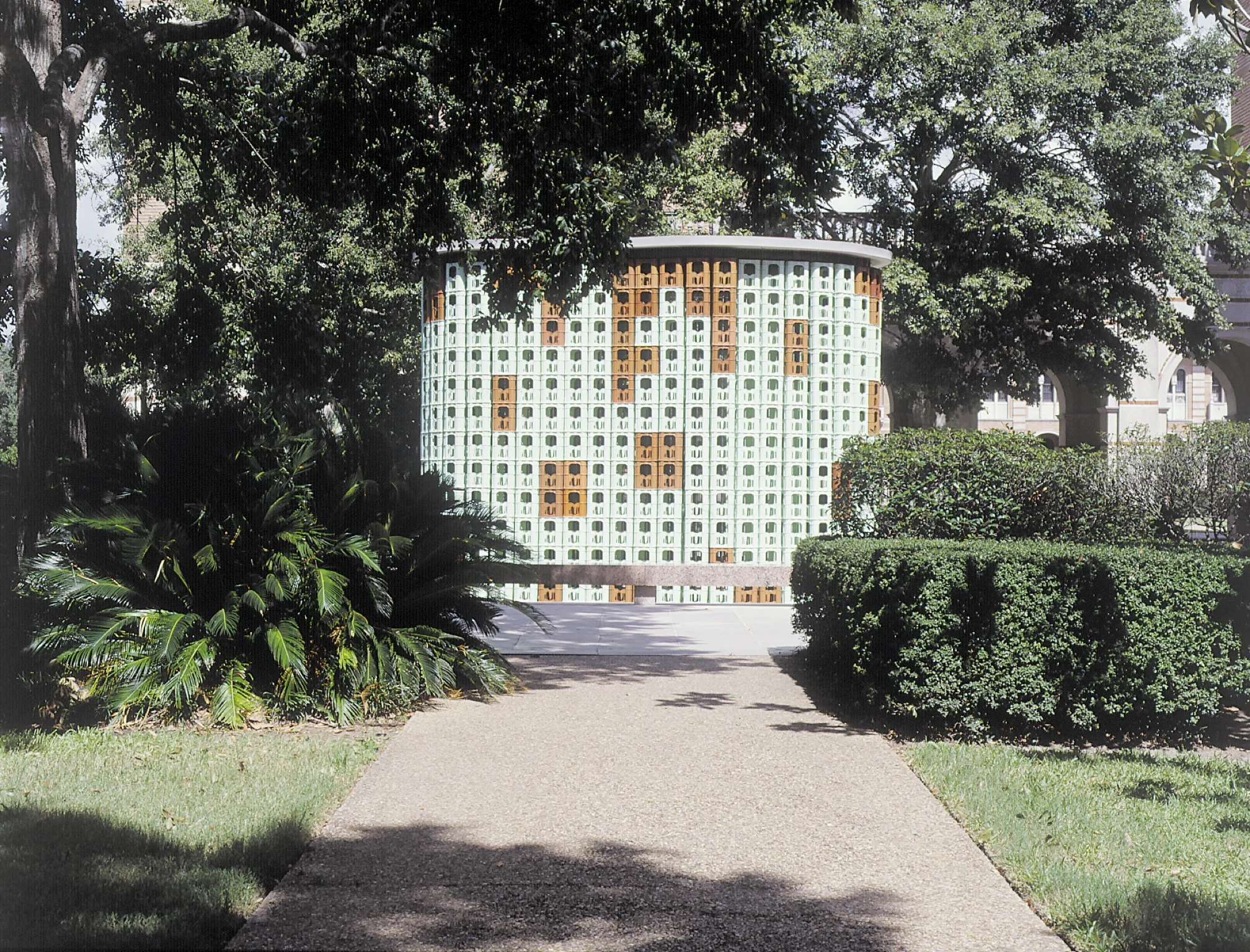

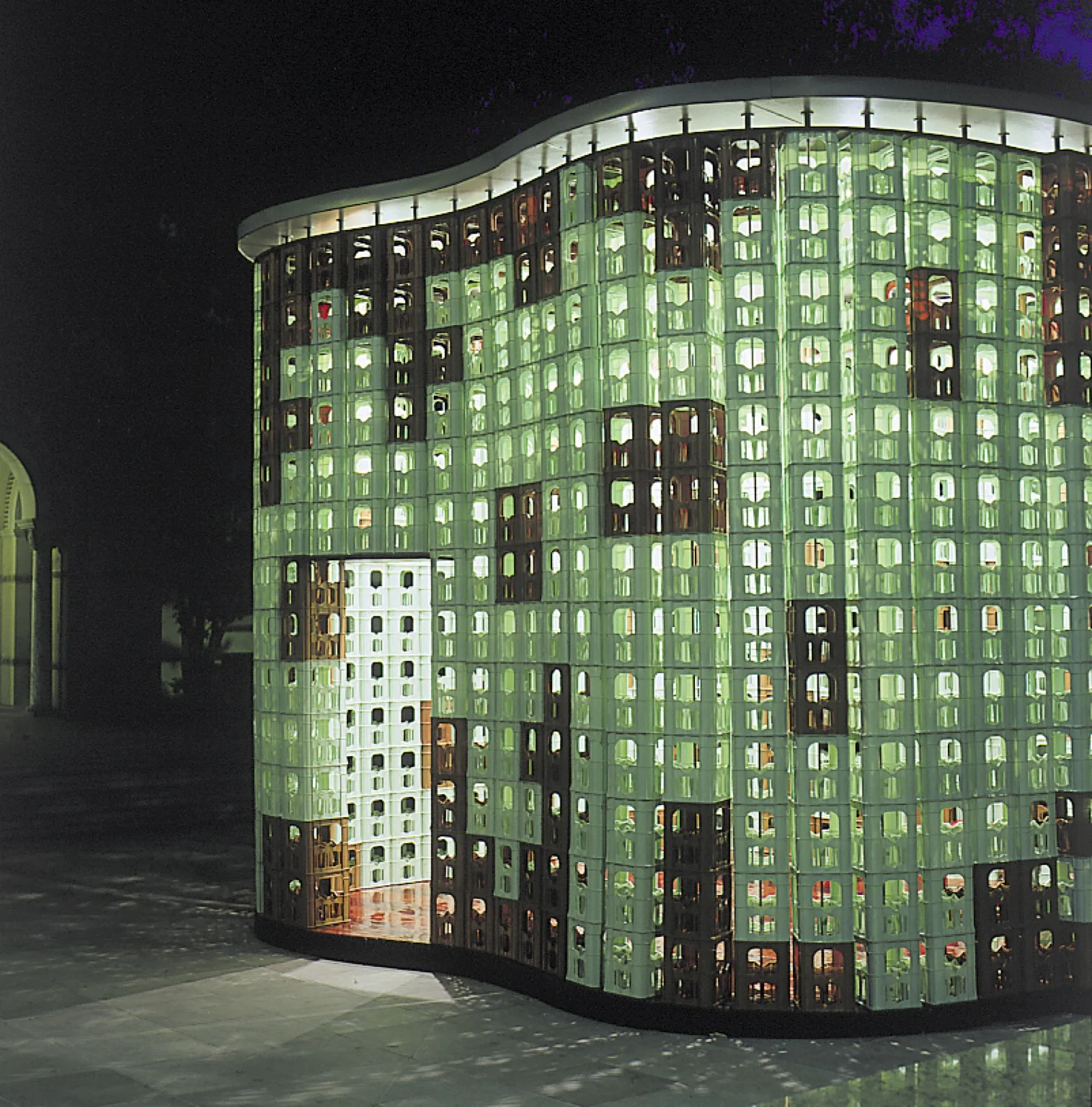

Winter and Hörbelt met as art students in Kassel, Germany where they discovered that they both sought to create art from everyday objects, and to invest their work with a functional value. The artists chose to work with beverage cases because of the cases’ inherent sculptural qualities, as well as their currency in everyday life. Traditionally, for a small deposit, Germans carry their water bottles home in crates, which they return later. The crates are reused, and the cycle is repeated endlessly. Winter and Hörbelt’s transformation of the crates into large-scale art objects temporarily removes them from this cycle, but they are always returned when the project is dismantled. Stacked to form walls, the openings in the sides of the crates permit continual passage of light and air. During the day, sunlight floods through the crates projecting patterns on the ground, while at night the internally lit structures glow like huge lanterns.

Winter and Hörbelt’s crate houses expand the boundaries of sculpture and architecture. They are beautiful, aesthetically appealing forms that can be experienced “inside-out,” and they are sites of dynamic public interaction. Both the social value and the artistic value of the crates are compounded in these new forms. The artists’ interest in the revitalization of public space is an engaging aspect of their work. During the 1997 Sculpture Project Münster, Winter/Hörbelt’s structures served as information booths; in 1999, they served as bus shelters in Havixbeck, and as a movie theater in Berlin. Wolfgang Winter notes, “Real places that bring people together, like the large old squares with their central, dominant sculptures, cannot grow forth as the products of some romantic longing, but must instead respond to modern needs and modes of perception.” By reaching out to viewers and making them active participants, Winter/Hörbelt’s crate houses creatively alter the aesthetic as well as the social structure of the environments in which they exist.